So, here we are - it's the end of another year, and traditionally a time to reflect and reminisce about the period that's just been since the last time we did this: what we've learnt, what we wished we'd known sooner, and the hopes we'll take with us into 2023...

Previously, I've approached this through looking at what generated the most interest/uproar across my social media channels, but this year I had the opportunity to spend a morning with fellow facilitators as part of an informal process with Paul Kelly and Caroline Jessop of IAF England and Wales fame.

Everyone in the session all seemed to agree how well structured it was, and how expertly guided we felt we'd been (possibly with the exception of Paul's ever-changing Christmas jumpers), and whilst others will be sharing on their own blogs, etc their views of it, I wanted to capture the reflections I took from it about myself and my business over the year that's been 2022, here:

CPD

I realise that the most beneficial things I've found this year with regards to my own professional CPD have been:

1) getting interviewed for various people's podcast series and radio shows* - it's a fascinating way to reflect on what I think I know, how I came to acquire this 'special knowledge', how it's influenced and continues to influence how I think, and so much more...

2) start a TikTok channel - like with interviews, it's such a wholly different way of having to approach how you think you know what you do; and with so much encouragement to indulge your creative impulses, I can see why some people are so deep into this social media channel...

NETWORKING

We often think of (formal) networking as a semi-regular forum or group we check-in with either virtually or in person. And reflecting on my involvement with several over the year has reminded me how important they are as a source of mutual and emotional encouragement.

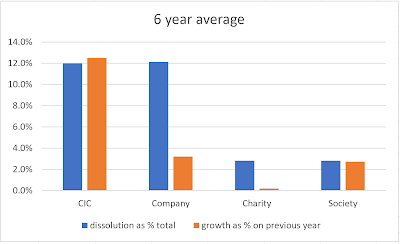

However, it also struck me that as valuable as such support is, it's usually with the same people (otherwise it wouldn't work) - what I've also experienced this year are a couple of 'exceptional events' (including being asked to draft an opinion piece on why CICs may have been the worst thing to have ever happened for the social enterprise movement, by an international media agency). These generated new opportunities to meet and speak with people who would normally be outside of my circles, and only with hindsight do I realise how reactionary I was in exploring these (note to self: be more organised and methodical next time!).

And whilst these new contacts are exciting, they're as equally scary (owing to the pay grade that some of these people operate at!), so knowing that there's a community I can check-back in with for some encouragement and assurance around them is important also...

WALKING

The session concluded with trying to look forwards, having now looking back - and generating an analogy for what we want to achieve in our business over the coming year.

Mine turned out to represent how I've always tried to approach my professional ways of working - walking:

- it's intentional; is recognised in supporting our well-being; allows us to explore new places; and has moments of serendipity in the people we encounter as we travel in this way.

- But of course, there's also a balance to this in that walking also always includes a risk that we might get lost, or find ourselves ill-prepared for rapidly changing circumstances (such as it starting to rain, but when we left it was sunny so we didn't bring a coat or brolly...)

Overall, it was a morning I'm glad I invested in with my peers, and will definitely be looking out for opportunities to again when the end of the years start to roll around again in 2023, 2024, 2025...

* podcasts and radio shows I've appeared on this year: